Yes the cornetto is insanely difficult to play, and that was also historically the case. It demands a ridiculously delicate approach to playing. Any force or tension or fatigue and the sound quality goes away. But when played well, it's absolutely unique, and was the king of instruments for several decades.

To address the initial question: it's not the easiest question to answer because documentation from the 15th century, when the trombone was invented, is both sparse and often not very precise. Iconography is not photography, and not always reliable, especially with new inventions the artists are not familiar with. In terms of surviving instruments there is only one brass instrument of any kind that survives from that century, so again limited information (it's a signal trumpet, and by chance it was exceptionally well preserved by being trapped in mud after it was thrown down in a castle's well along with guns and weapons, likely to avoid them being taken by an enemy force). You need to look at the overall historical context and what came before.

What the the various evidence very strongly suggests is that in the 15th century, slide trumpets were used in the "loud bands" of the time, along with shawms and bombards, the loud double reed instruments. Earlier, those reeds instruments would have sometimes played with one or more long trumpet, the bombard playing a "tenor", basically a known tune, and the shawm improvising a higher countermelody, while the trumpet(s), limited to the harmonic series, would provide a rhythmical drone. By the fifteenth century, you would typically now have two lines against the tenor, this additional third voice being more or less in the same range as the tenor. And to play that third moving voice they added a single telescoping tube to trumpets. Those bands served a variety of functions, from playing from city walls and towers to signal time and announcements, to providing entertainment at banquets, notably as basically a dance band. They were multiinstrumentalists and played a variety of instruments aside from the reeds and trumpets, also bagpipes and percussions and crumhorns and various other loud wind instruments. The cornetto also appears to have initially started as one of those loud instruments, around the same time as the trombone.

It is very likely that the trombone evolved from the slide trumpet together with (or because of) the addition to the polyphonic texture of a fourth, definitely lower, voice: the bass. A slide trumpet has about the tubing length of an alto trombone, and only has about four semitones on the slide, so its low range is not really usable, with some very large gaps. Its practical range is really around

to

, roughly, with also a few lower notes available when needed (with a gap in-between), and for sure nothing below A. So it definitely doesn't work as a proper bass instrument. It seems likely that they experimented with various ways to make the trumpet longer and lower pitched (there is iconography of instruments that appear to have a single slide but are much longer than you would expect from a slide trumpet, with tubing extending past the player's head, of course those could just be poorly drawn slide trumpets or trombone, but a hypothetical longer trumpet is also a logical step). But the lower it is, the fewer positions it has, and you never reach a satisfactory solution, until you come up with the double, U-shaped slide, and the trombone is born. That is around 1450.

The trombone and cornett very quickly proved to be more versatile and not only able to play loud, but also very quiet and in a way that worked very well with voices, and they started being used in church as well, a role it has managed to continuously keep, in at least some places. That versatility is one of the key factors that explains the instrument's success. Within a hundred years of its inception you see trombones used in a tremendous variety of situations, still playing with the loud band, and with singers in church, but also mentioned as an option for the bass of the flute or recorder consorts, for example, or even described playing in chamber settings with a flute, a harp. It could play loud and soft, it could do fast notes but also hold very long notes, it could play chromatically over a very wide range, it could be used as a bass, tenor or alto instrument (already before the bass and alto trombones appeared) and it could transpose without causing problems with intonation. It could be trumpetty and clear from a distance outdoors, or extremely refined and subtle in its imitation of the inflections of the voice.

It's important to note that music wasn't "made for it" at first, and composers didn't write "for it", or for any other instrument for that matter. For the most part, composers or transcribers didn't start specifying instrumentation until the late 16th century, and even then it usually stayed very flexible until well into the baroque era. Performers (and leaders) chose what instruments were used when and for what. And so they wouldn't have used the trombone if they couldn't play it well for the contexts they wanted to use it in. They chose to use it in so many different situations because it was so well-suited for all of them, and clearly there were capable players around.

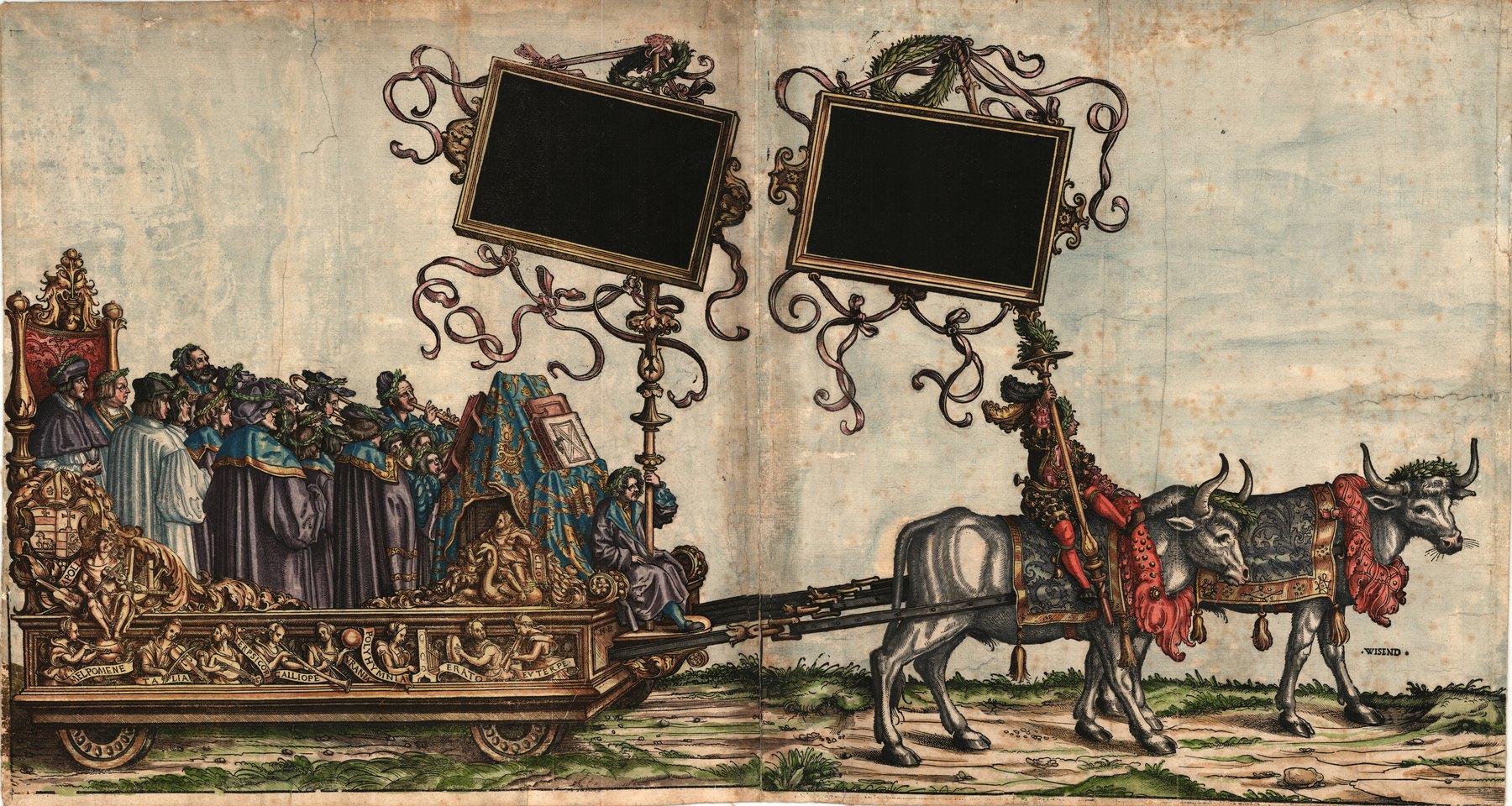

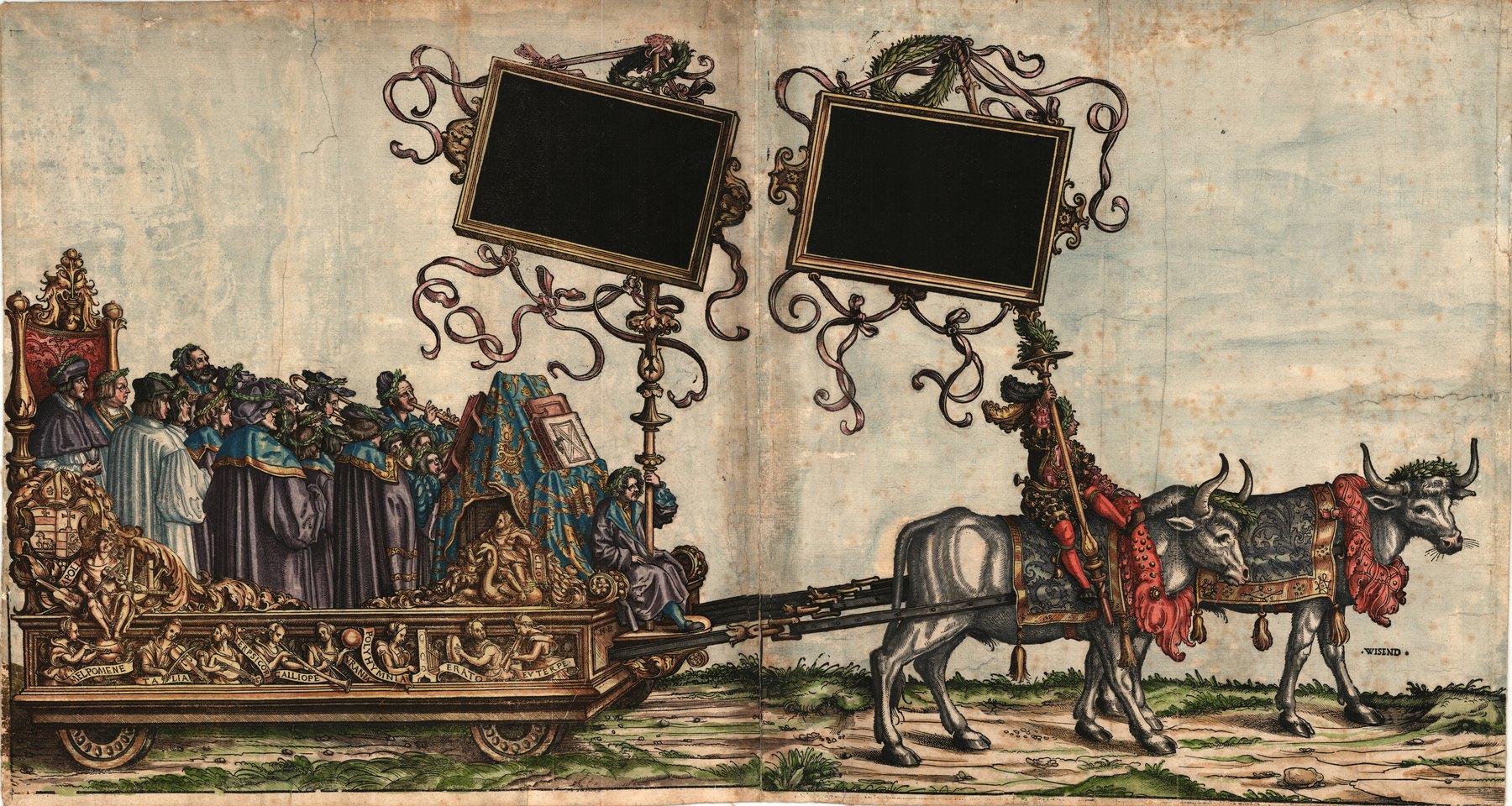

As to how people became good at it, you have to remember that people back then, especially lay people, didn't have school to attend for most of their first 20+ years (and they also had far fewer distractions to occupy themselves with). They were instead usually trained from a very young age for a specific job. If you were a professional wind instrument player, you were probably born from a family of musicians, would have trained your whole life, from early childhood, and would learn a large number of instruments to a very high level. So picking up this new instrument would not have been particularly challenging (especially if you're already proficient on the slide trumpet, which is harder to play). You also didn't have to learn all of the musical styles and languages that didn't exist yet. Only the language and style of the time, which they would have known and understood extremely well. I can easily see how a few particularly gifted players would have emerged early on and established a reference level for others to follow. In fact we have the names of some of those, for example Augustin Schubinger, Hans Neuschel and Hans Stewdl, all trombonists who were members of or regularly played for the bands of the imperial court of Maximilian I (although Schubinger became particularly famous more as a cornettist), and are featured and named in the famous "Triumphzug Maximilians".

Here's Schubinger (on cornett) and Stewdl (trombone) depicted playing with the

cantorey

And Neuschel (trombone) depicted leading the loud band