The Mystery of the Missing Equali

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

The first trombone Equali we're familiar with are Beethoven's (1812). The last are Bruckner's (1847). That is the 19th Century.

If you try to read about the equali form you will encounter references, of course, to Beethoven and Bruckner and assertions that they were in the long tradition of somber trombone music for funerals and church use.

Typical, from Wikipedia: "In the 18th century the equale became established as a generic term for short, chordal pieces for trombone choirs, usually quartets or trios...."

Note that that time frame can not include any of the pieces we know today. By whom and where are those 18th century equali?

There doesn't seem to be any 18th Century evidence for 18th Century equali.

If you try to read about the equali form you will encounter references, of course, to Beethoven and Bruckner and assertions that they were in the long tradition of somber trombone music for funerals and church use.

Typical, from Wikipedia: "In the 18th century the equale became established as a generic term for short, chordal pieces for trombone choirs, usually quartets or trios...."

Note that that time frame can not include any of the pieces we know today. By whom and where are those 18th century equali?

There doesn't seem to be any 18th Century evidence for 18th Century equali.

-

ttf_hyperbolica

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:53 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

If you think of equali as any piece written for groups of any instrument or voice, then any mens choir, trombone, shawm, serpent or recorder ensemble of the same pitch would be an equali. Google is probably not the best measure of historic works. Don't we have a couple music historians around here.?

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

IMSLP has many obscure composers and works but I can find nothing called an "Equali" or any of the variant spellings, for trombones or any other instrumentation or voices, prior to Beethoven.

-

ttf_hyperbolica

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:53 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: robcat2075 on Nov 09, 2017, 10:27AMIMSLP has many obscure composers and works but I can find nothing called an "Equali" or any of the variant spellings, for trombones or any other instrumentation or voices, prior to Beethoven.

I don't doubt that. What I'm saying is to think of "equali" as a form rather than a title. Not all lieder are called "lieder".

I don't doubt that. What I'm saying is to think of "equali" as a form rather than a title. Not all lieder are called "lieder".

-

ttf_BillO

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: hyperbolica on Nov 09, 2017, 10:12AMIf you think of equali as any piece written for groups of any instrument or voice, then any mens choir, trombone, shawm, serpent or recorder ensemble of the same pitch would be an equali. Google is probably not the best measure of historic works. Don't we have a couple music historians around here.?

I think you are right. They would not even have to be of the same pitch, but would need to be scored closely together. I think the term was used mainly academically. Today we'd refer to them as small ensemble choirs like trombone quartet or sax trio, or something of that nature. They could even be a movement of or other small part of a larger composition.

I think you are right. They would not even have to be of the same pitch, but would need to be scored closely together. I think the term was used mainly academically. Today we'd refer to them as small ensemble choirs like trombone quartet or sax trio, or something of that nature. They could even be a movement of or other small part of a larger composition.

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: hyperbolica on Nov 09, 2017, 10:39AMI don't doubt that. What I'm saying is to think of "equali" as a form rather than a title. Not all lieder are called "lieder".

That's valid.

There is a category of "for 4 equal voices", one entry does indeed precede Beethoven and fits the Wiki definition above.

(get a load of the notation. A whole note on a bar line. Too lazy to tie two halves)

I'm going to say the lyrics are so integral to that that it didn't inform any part of a trombone tradition.

are so integral to that that it didn't inform any part of a trombone tradition.

It's possible there are more, but if they were such a crucial trombone tradition, why aren't we playing them when we are so eager for examples of trombone music from that period?

That's valid.

There is a category of "for 4 equal voices", one entry does indeed precede Beethoven and fits the Wiki definition above.

(get a load of the notation. A whole note on a bar line. Too lazy to tie two halves)

I'm going to say the lyrics

are so integral to that that it didn't inform any part of a trombone tradition.

are so integral to that that it didn't inform any part of a trombone tradition.It's possible there are more, but if they were such a crucial trombone tradition, why aren't we playing them when we are so eager for examples of trombone music from that period?

-

ttf_kbiggs

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:53 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: BillO on Nov 09, 2017, 11:04AMI think the term was used mainly academically.

My trombone quartet played several equali in our last concert. We chose composers other than Beethoven or Bruckner. From my amateur research, I remember the term originated in the 18th century, but the origins were unknown. I don’t remember it being used academically or strictly academically. After all, Bruckner and Beethoven weren’t academics, but they were familiar enough with the term to use for similar pieces over a 30- or 40-year gap. Descriptively (or functionally), it’s come to mean an instrumental (occasionally choral) chamber work of short duration, often in a slow tempo and somber mood, but not always. Usually homophonic and chorale-like, with little in the way of counterpoint.

Quote from: BillO on Nov 09, 2017, 11:04AMThey could even be a movement of or other small part of a larger composition.

I doubt it. Equali were usually independent compositions.

Theoretically, you might take an excerpt from a larger composition and call it an equali. Example: the trombone quintet from Monteverdi’s Orfeo (1607, 1609, 1615), act 4. Orfeo (Orpheus) looks back to see whether his beloved Euridice is following him so she can escape Hell and follow him to the surface. In looking back, he loses his agreement with Plutone (Pluto, ruler of Hell) to trust the gods. Once Orfeo realizes what he’s done, the trombone quintet intones a somber chorale-like piece, about 11 or 12 bars in length, to emphasize the consequences of his action.

While this little piece could be excerpted and played on its own as an equali, that wasn’t the intent of Monteverdi, and doesn’t seem to be the purpose of writing an equali.

My trombone quartet played several equali in our last concert. We chose composers other than Beethoven or Bruckner. From my amateur research, I remember the term originated in the 18th century, but the origins were unknown. I don’t remember it being used academically or strictly academically. After all, Bruckner and Beethoven weren’t academics, but they were familiar enough with the term to use for similar pieces over a 30- or 40-year gap. Descriptively (or functionally), it’s come to mean an instrumental (occasionally choral) chamber work of short duration, often in a slow tempo and somber mood, but not always. Usually homophonic and chorale-like, with little in the way of counterpoint.

Quote from: BillO on Nov 09, 2017, 11:04AMThey could even be a movement of or other small part of a larger composition.

I doubt it. Equali were usually independent compositions.

Theoretically, you might take an excerpt from a larger composition and call it an equali. Example: the trombone quintet from Monteverdi’s Orfeo (1607, 1609, 1615), act 4. Orfeo (Orpheus) looks back to see whether his beloved Euridice is following him so she can escape Hell and follow him to the surface. In looking back, he loses his agreement with Plutone (Pluto, ruler of Hell) to trust the gods. Once Orfeo realizes what he’s done, the trombone quintet intones a somber chorale-like piece, about 11 or 12 bars in length, to emphasize the consequences of his action.

While this little piece could be excerpted and played on its own as an equali, that wasn’t the intent of Monteverdi, and doesn’t seem to be the purpose of writing an equali.

-

ttf_MrPillow

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 12:00 pm

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Which equali did you perform that were by other composers?

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

I will pedantically note  that Bruckner was an academic. He spent a lot of his life pursuing degrees and certifications and taught music theory for 20+ years in Vienna.

that Bruckner was an academic. He spent a lot of his life pursuing degrees and certifications and taught music theory for 20+ years in Vienna.

I have no idea if he was aware of Beethoven's Equali prior to writing his own.

that Bruckner was an academic. He spent a lot of his life pursuing degrees and certifications and taught music theory for 20+ years in Vienna.

that Bruckner was an academic. He spent a lot of his life pursuing degrees and certifications and taught music theory for 20+ years in Vienna.I have no idea if he was aware of Beethoven's Equali prior to writing his own.

-

ttf_BillO

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: kbiggs on Nov 09, 2017, 11:37AMMy trombone quartet played several equali in our last concert. We chose composers other than Beethoven or Bruckner. From my amateur research, I remember the term originated in the 18th century, but the origins were unknown. I dont remember it being used academically or strictly academically. After all, Bruckner and Beethoven werent academics, but they were familiar enough with the term to use for similar pieces over a 30- or 40-year gap. Descriptively (or functionally), its come to mean an instrumental (occasionally choral) chamber work of short duration, often in a slow tempo and somber mood, but not always. Usually homophonic and chorale-like, with little in the way of counterpoint. Not sure I agree with you. Beethoven was a student of Neefer and a teacher of Czerny as well as others. Bruckner was a noted student of music, despite being trained as a music teacher and later returning to music teaching at the Vienna Conservatory. Nevertheless, what I meant by being used academically was it was liekly not used in common language by the layperson, but rather by those well versed in musical theory.

QuoteI doubt it. Equali were usually independent compositions.

Theoretically, you might take an excerpt from a larger composition and call it an equali. Example: the trombone quintet from Monteverdis Orfeo (1607, 1609, 1615), act 4. Orfeo (Orpheus) looks back to see whether his beloved Euridice is following him so she can escape Hell and follow him to the surface. In looking back, he loses his agreement with Plutone (Pluto, ruler of Hell) to trust the gods. Once Orfeo realizes what hes done, the trombone quintet intones a somber chorale-like piece, about 11 or 12 bars in length, to emphasize the consequences of his action.

While this little piece could be excerpted and played on its own as an equali, that wasnt the intent of Monteverdi, and doesnt seem to be the purpose of writing an equali.

Again I have to disagree. The word equali does not describe a piece. It is not like 'concerto' or 'overture', it is a musical style - Equal Voices - close harmonies - like barbershop is a 'style' and not a 'piece'. The piece you mention could indeed be in the equali style, and would be whether you perform it as part of the whole work, or by itself.

QuoteI doubt it. Equali were usually independent compositions.

Theoretically, you might take an excerpt from a larger composition and call it an equali. Example: the trombone quintet from Monteverdis Orfeo (1607, 1609, 1615), act 4. Orfeo (Orpheus) looks back to see whether his beloved Euridice is following him so she can escape Hell and follow him to the surface. In looking back, he loses his agreement with Plutone (Pluto, ruler of Hell) to trust the gods. Once Orfeo realizes what hes done, the trombone quintet intones a somber chorale-like piece, about 11 or 12 bars in length, to emphasize the consequences of his action.

While this little piece could be excerpted and played on its own as an equali, that wasnt the intent of Monteverdi, and doesnt seem to be the purpose of writing an equali.

Again I have to disagree. The word equali does not describe a piece. It is not like 'concerto' or 'overture', it is a musical style - Equal Voices - close harmonies - like barbershop is a 'style' and not a 'piece'. The piece you mention could indeed be in the equali style, and would be whether you perform it as part of the whole work, or by itself.

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

No, the sense I get from what is written about "equali" is that it's not a style but a category of music compositions.

For solemn occasions (not just funerals)

Played in churches

Equal voices

Stand alone, not part of larger works containing non-equali type music

It's a category like "minuet" or "fugue" or "air". Those are not titles, and not really styles. But people do talk about them and we know they existed before Beethoven. Not so for "equali"

Here is a page from "Musical Times" in 1898 which seems to be the first published account of the circumstances surrounding Beethoven's Equale.

The three equali came to prominence then because they were played at William Gladstone's funeral.

It admits, in 1898, the origin of the term is "unknown" and then says that "it has come to signify" a piece for trombones played at "great funerals" but provides no source for that.

I propose that everything we "know" about Equali comes from this 1898 article and that years of misremembering and misquoting it has grown a legend about equali for trombones that can't be substantiated with actual music from before Beethoven.

Unless someone can produce music that was somehow identified or referred to as being "equali"?

For solemn occasions (not just funerals)

Played in churches

Equal voices

Stand alone, not part of larger works containing non-equali type music

It's a category like "minuet" or "fugue" or "air". Those are not titles, and not really styles. But people do talk about them and we know they existed before Beethoven. Not so for "equali"

Here is a page from "Musical Times" in 1898 which seems to be the first published account of the circumstances surrounding Beethoven's Equale.

The three equali came to prominence then because they were played at William Gladstone's funeral.

It admits, in 1898, the origin of the term is "unknown" and then says that "it has come to signify" a piece for trombones played at "great funerals" but provides no source for that.

I propose that everything we "know" about Equali comes from this 1898 article and that years of misremembering and misquoting it has grown a legend about equali for trombones that can't be substantiated with actual music from before Beethoven.

Unless someone can produce music that was somehow identified or referred to as being "equali"?

-

ttf_BillO

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

I think you're inferring a lot from the few pieces named "Equali" and the limited writing on this. I don't think this is a valid approach given the little information we have.

Here: https://archive.org/stream/5000musicalterms00adamuoft#page/52/mode/2up we have the definition of the term Equal Voices - the English term. It leaves things a bit more open.

Other than the very few known equali of Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Bruckner we have little to go on pertaining to the actual use of such compositions.

The Wiki article offers this:

"Stravinsky scored In memoriam Dylan Thomas, his setting of "Do not go gentle into that good night", for tenor, string quartet and four trombones, which may be an "echo" of the tradition."

And there is the piece kbiggs alluded to.

If we assume equali were written for trombone only, and the only examples are those of Beethoven, Mendelssohn (Wittmann) and Bruckner, then your inference may be correct. However, I'm not yet ready to accept those confines.

But then we have this from fsung: http://tromboneforum.org/index.php/topic,102941.msg1219979.html#msg1219979 which implies the Mendelssohn pieces were just transcriptions by Gustave Wittmann of music Mendelssohn never referred to as equali. He called them "Songs for four-part male choir". In fact, some of his songs for four-part male choir (and there were a few) are definitely not overly solemn, but he drew no distinction between them. That's a matter of interpretation though.

It's all so inconclusive.

I'm going to keep an open mind on this until I see more information.

Here: https://archive.org/stream/5000musicalterms00adamuoft#page/52/mode/2up we have the definition of the term Equal Voices - the English term. It leaves things a bit more open.

Other than the very few known equali of Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Bruckner we have little to go on pertaining to the actual use of such compositions.

The Wiki article offers this:

"Stravinsky scored In memoriam Dylan Thomas, his setting of "Do not go gentle into that good night", for tenor, string quartet and four trombones, which may be an "echo" of the tradition."

And there is the piece kbiggs alluded to.

If we assume equali were written for trombone only, and the only examples are those of Beethoven, Mendelssohn (Wittmann) and Bruckner, then your inference may be correct. However, I'm not yet ready to accept those confines.

But then we have this from fsung: http://tromboneforum.org/index.php/topic,102941.msg1219979.html#msg1219979 which implies the Mendelssohn pieces were just transcriptions by Gustave Wittmann of music Mendelssohn never referred to as equali. He called them "Songs for four-part male choir". In fact, some of his songs for four-part male choir (and there were a few) are definitely not overly solemn, but he drew no distinction between them. That's a matter of interpretation though.

It's all so inconclusive.

I'm going to keep an open mind on this until I see more information.

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Inferring is all we can do until someone starts finding actual evidence of anything "equali" prior to Beethoven.

Published pieces, mentions of pieces, even a use of the term in some sense similar to what we are using it for now... it seems not to really exist.

Wikipedia says "equali" was a term of 16th century music theorists but the citation goes nowhere.

Using Google's ngram viewer, in the years 1500-1800, I can't find any musical-context use of "equali" or "equale" in English, Italian or German and only one possibly musical use of it a French book of poetry.

The Stravinsky piece (1954) "may be," possibly, his imaginative notion of solemn trombone music but we can't take it as any evidence of pre-Beethoven music making.

Published pieces, mentions of pieces, even a use of the term in some sense similar to what we are using it for now... it seems not to really exist.

Wikipedia says "equali" was a term of 16th century music theorists but the citation goes nowhere.

Using Google's ngram viewer, in the years 1500-1800, I can't find any musical-context use of "equali" or "equale" in English, Italian or German and only one possibly musical use of it a French book of poetry.

The Stravinsky piece (1954) "may be," possibly, his imaginative notion of solemn trombone music but we can't take it as any evidence of pre-Beethoven music making.

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

More mystery...

It turns out "equale" is not an Italian word that means "equal". It means "and which" according to Google translate.

That Italian word is "eguale" and that is in the noun sense like , "we are equals"

"Eguali" would be the plural.

It turns out "equale" is not an Italian word that means "equal". It means "and which" according to Google translate.

That Italian word is "eguale" and that is in the noun sense like , "we are equals"

"Eguali" would be the plural.

-

ttf_MrPillow

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 12:00 pm

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

I seem to recall it being derived from the Latin Æquale, not the Italian.

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: MrPillow on Nov 09, 2017, 07:55PMI seem to recall it being derived from the Latin Æquale, not the Italian.

That would explain Bruckner's spelling.

A cursory look through book titles that have that word in them is as bleak as for the other spellings... it seems to be used mostly in a math/algebra/geometry frame.

We still lack an actual 18th century use of the term in a musical context.

That would explain Bruckner's spelling.

A cursory look through book titles that have that word in them is as bleak as for the other spellings... it seems to be used mostly in a math/algebra/geometry frame.

We still lack an actual 18th century use of the term in a musical context.

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Here's a thought experiment...

Is there any other musical term that we are sure was being used in the 18th century even though no 18th century evidence of its use exists?

Is there any other musical term that we are sure was being used in the 18th century even though no 18th century evidence of its use exists?

-

ttf_kbiggs

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:53 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: MrPillow on Nov 09, 2017, 11:57AMWhich equali did you perform that were by other composers?

Wenzel Lambel, 19th c.

Robert (?) Newton, 21st c.

There was another composer but I cant remember now who. Some of the Lambel equali were different than the Beethoven or Bruckner equaliextended pieces of 3-4 minutes including a repeat, some solo and duet passages of 3-4 bars at a time.

Wenzel Lambel, 19th c.

Robert (?) Newton, 21st c.

There was another composer but I cant remember now who. Some of the Lambel equali were different than the Beethoven or Bruckner equaliextended pieces of 3-4 minutes including a repeat, some solo and duet passages of 3-4 bars at a time.

-

ttf_kbiggs

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:53 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

This thread reminds me of the joke about the musicologists convention...

One evening, after the papers had been presented and the participants had retired to the local drinking establishment to imbibe their favorite beverages (rosé, claret, chablis, etc.), the conversation eventually came around to 18th and 19th century European composers. At one point, someone mentioned the name Beethoven.

Conversation stopped.

Beethoven? someone asked.

The name was murmured around the room, all questioning who this Beethoven could be.

Conversation started to pick up again when, all of a sudden, from a dark corner of the room, came the question, Beethoven? He was a student of Albrechtsberger, wasnt he?

The replies were swift and congratulatory: Why, of course! Indeed, how silly of me to forget! By Jove, thats the ticket! Good job, I say! Mind like a steel trap, he has!

One evening, after the papers had been presented and the participants had retired to the local drinking establishment to imbibe their favorite beverages (rosé, claret, chablis, etc.), the conversation eventually came around to 18th and 19th century European composers. At one point, someone mentioned the name Beethoven.

Conversation stopped.

Beethoven? someone asked.

The name was murmured around the room, all questioning who this Beethoven could be.

Conversation started to pick up again when, all of a sudden, from a dark corner of the room, came the question, Beethoven? He was a student of Albrechtsberger, wasnt he?

The replies were swift and congratulatory: Why, of course! Indeed, how silly of me to forget! By Jove, thats the ticket! Good job, I say! Mind like a steel trap, he has!

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

I believe these things to be true...

- the original manuscript is lost

- No one actually says the word "Equale" appeared on it.

- The only claim is that Beethoven "inscribed" on it, "Linz, den 2ten 9ber, 1812". That's not the day he wrote it, that is the day it was for, aka All Soul's Day.

-The first publication of this music (Haslinger, 1827) in any form, a men's chorus adaptation created for Beethoven's funeral, does not use the word "Equale".

-The trombone-only version is not published until 1888 (Breitkopf & Hartel). This is the first time Beethoven's work is labeled "Equale"

-The explanation in the 1898 The Musical Times article of what "Equale" means is informed only by its usage in the 19th century and has since been wrongly assumed as evidence of "equale" being a musical genre prior to Beethoven.

The easiest way to disprove my thesis is to find...

-the Beethoven manuscript and see it really has "Drei Equale fur vier Posaunen" on it.

-a pre-Beethoven piece of music labeled as an "equale"

-a pre-Beethoven written reference to such a work

-a pre-Beethoven discussion of "equale" as a genre.

- the original manuscript is lost

- No one actually says the word "Equale" appeared on it.

- The only claim is that Beethoven "inscribed" on it, "Linz, den 2ten 9ber, 1812". That's not the day he wrote it, that is the day it was for, aka All Soul's Day.

-The first publication of this music (Haslinger, 1827) in any form, a men's chorus adaptation created for Beethoven's funeral, does not use the word "Equale".

-The trombone-only version is not published until 1888 (Breitkopf & Hartel). This is the first time Beethoven's work is labeled "Equale"

-The explanation in the 1898 The Musical Times article of what "Equale" means is informed only by its usage in the 19th century and has since been wrongly assumed as evidence of "equale" being a musical genre prior to Beethoven.

The easiest way to disprove my thesis is to find...

-the Beethoven manuscript and see it really has "Drei Equale fur vier Posaunen" on it.

-a pre-Beethoven piece of music labeled as an "equale"

-a pre-Beethoven written reference to such a work

-a pre-Beethoven discussion of "equale" as a genre.

-

ttf_MrPillow

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 12:00 pm

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

This compilation dated to 1583, towards the end of its lengthy title, states that it includes "other magnificats [and?] aequales" - http://stimmbuecher.digitale-sammlungen.de/view?id=bsb00075343

-

ttf_BillO

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Cool! Thanks.

Did you change jobs again?

Did you change jobs again?

-

ttf_MrPillow

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 12:00 pm

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

I'm on a 1-year contract with The Preservation Society of Newport County. No trombones here sadly

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: MrPillow on Nov 10, 2017, 04:39PMThis compilation dated to 1583, towards the end of its lengthy title, states that it includes "other magnificats [and?] aequales" - http://stimmbuecher.digitale-sammlungen.de/view?id=bsb00075343

Hooray!

It is a use of the word.

"ad" means "to" as in "Gradus ad Parnassum"

"Magnificat ad aequale" = [from] Magnificat to aequale (?)

But is is curious that it is not capitalized like nouns are in the rest of that title (German rule) as if it's a modifier.

Inside it is always used as "Ad aequales"

Hooray!

It is a use of the word.

"ad" means "to" as in "Gradus ad Parnassum"

"Magnificat ad aequale" = [from] Magnificat to aequale (?)

But is is curious that it is not capitalized like nouns are in the rest of that title (German rule) as if it's a modifier.

Inside it is always used as "Ad aequales"

-

ttf_MrPillow

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 12:00 pm

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Perhaps then a description of the arrangement of voices within a work, in this case, the magnificat?

-

ttf_BillO

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Can anyone determine who the composer was?

-

ttf_MrPillow

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 12:00 pm

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Ioannes Baptista Pinellus AKA Giovanni Pinello.

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

That Shakespearean German doesn't quite work in Google Translate

My rough guess...

German Magnificat in the eight musical tones (modes?)

each one twice

and [s]wandering/traveling(?)[/s] ninth modes three times

with four and five voices

several new(?) Benedictions

very lovely to sing

and on all instruments to play

and others too

Magnificat to aequales

Many of these pieces span a tenor trombone range ...

to

to

My rough guess...

German Magnificat in the eight musical tones (modes?)

each one twice

and [s]wandering/traveling(?)[/s] ninth modes three times

with four and five voices

several new(?) Benedictions

very lovely to sing

and on all instruments to play

and others too

Magnificat to aequales

Many of these pieces span a tenor trombone range ...

to

to

-

ttf_BillO

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: MrPillow on Nov 10, 2017, 06:00PMIoannes Baptista Pinellus AKA Giovanni Pinello.

Does not look like he made this list: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Magnificat_composers

Is there a good reference to his musical notation? I'm a little confused. No bar lines, and I 'm not sure of the times signatures or the clefs. I'd like to take a swat at transcription

Does not look like he made this list: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Magnificat_composers

Is there a good reference to his musical notation? I'm a little confused. No bar lines, and I 'm not sure of the times signatures or the clefs. I'd like to take a swat at transcription

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: BillO on Nov 10, 2017, 08:06PMDoes not look like he made this list: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Magnificat_composers

Is there a good reference to his musical notation? I'm a little confused. No bar lines, and I 'm not sure of the times signatures or the clefs. I'd like to take a swat at transcription

barlines?

The ones with just C clefs on all four parts are easier to negotiate. The tricky part is the rests. The are sometimes just the barest speck of ink on the staff.

an X is a sharp, I think.

the square whole note is equal to two whole notes and the square whole note with a stem is four whole notes.

Several seem to start with a solo chant in the top voice that is not accounted for in the other parts.

Is there a good reference to his musical notation? I'm a little confused. No bar lines, and I 'm not sure of the times signatures or the clefs. I'd like to take a swat at transcription

barlines?

The ones with just C clefs on all four parts are easier to negotiate. The tricky part is the rests. The are sometimes just the barest speck of ink on the staff.

an X is a sharp, I think.

the square whole note is equal to two whole notes and the square whole note with a stem is four whole notes.

Several seem to start with a solo chant in the top voice that is not accounted for in the other parts.

-

ttf_Le.Tromboniste

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:59 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: BillO on Nov 10, 2017, 08:06PMDoes not look like he made this list: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Magnificat_composers

Is there a good reference to his musical notation? I'm a little confused. No bar lines, and I 'm not sure of the times signatures or the clefs. I'd like to take a swat at transcription

Quote from: robcat2075 on Nov 10, 2017, 08:34PMbarlines?

The ones with just C clefs on all four parts are easier to negotiate. The tricky part is the rests. The are sometimes just the barest speck of ink on the staff.

an X is a sharp, I think.

the square whole note is equal to two whole notes and the square whole note with a stem is four whole notes.

Several seem to start with a solo chant in the top voice that is not accounted for in the other parts.

I didn't go through the whole book so I'm not discussing any specific case, but about mensural notation on general :

No barlines is standard (although typically bassus pro organo / partitura parts often do have barlines, although not necessarily consistently or of equal length.)

Robert's note values are correct, for duple meters. In triple time, though, a brevis (square) is divided in 3 semibrevis (whole notes) in tempus perfectum prolatio minor (à circle, or the semibrevis is divided in 3 minime (half notes) in tempus imperfectum prolatio maior (a C with a dot in the middle), or more rarely both, in tempus perfectum prolatio maior (circle with a dot in the middle).

Then there are a bunch of rules that temper that, for example in tempus perfectum a semibrevis after a brevis "imperfects" it (makes it 2 long instead of 3),so a brevis followed by a semibrevis is 2+1. In some cases a semibrevis before a brevis does that too (so it's 1+2), and in some cases, two semibrevis in row will have the second "altered", meaning doubled (also 1+2). It would be hard to explain all these rules in a forum post and they might not all be relevant as this is a rather late source. Black filled notes are always imperfect (duple). (here I notice many pieces start with a solo voice singing a line in black notation - that is chant, as Robert said. It is sometimes accounted for in other parts with rests, sometimes not).

A narrow square note with a stem is a longa (4 whole notes), a wide square note with a stem is a maxima (8 whole notes).

I notice there are ligatures. Those can be rather complex but I've only seen short two note ones in here. Ligatures that have a stem up are always whole-whole. For the others it depends on the shape, direction of motion, and where the last note is relative to the final stem (when there is one).

Note that it is common that not all voices reach the final note at the same time. Those who finish earlier just hang on to their final note until everyone is done.

X is sharp or natural, depending (a B or E with an x is natural, not sharp). Accidentals are rarely used because performers knew where to use them (e.g. sharpen the leading note at cadence, make some Bs and Es flat following the rules of solmisation, etc). They are used inconsistently in written form.

Clefs are the usual F, C and G clefs, except they can be on any line. Standard clef configuration is Soprano Alto Tenor Bass (C1, C3, C4, F4). I notice that some pieces (the very first one for instance) are in what is called "chiavette", literally the "little clefs" - Treble, mezzo soprano, alto, tenor or baritone (G2, C2, C3, C4 or F3). This is generally accepted to mean it would have been transposed down (any piece could be transposed up or down at will, but chiavette often implies it hasto be, and typically by larger transposition interval - down a fourth, fifth, sixth or seventh).

Rests are the hardest part of sight reading music like that (because of the absence of barlines) but are actually the most familiar notation. They are the same we use today. A brevis (square) rest fills the interval between two lines, a longa rest (or two breve) fills two spaces. As we're used to, a semibrevis (whole) rest hangs from the line and minima (half) rest stands on a line - they're just slimmer than the modern version - a semiminima (quarter) rest hooks to the right, and a fusa (8th) rest hooks to the left.

Hope it helped.

Is there a good reference to his musical notation? I'm a little confused. No bar lines, and I 'm not sure of the times signatures or the clefs. I'd like to take a swat at transcription

Quote from: robcat2075 on Nov 10, 2017, 08:34PMbarlines?

The ones with just C clefs on all four parts are easier to negotiate. The tricky part is the rests. The are sometimes just the barest speck of ink on the staff.

an X is a sharp, I think.

the square whole note is equal to two whole notes and the square whole note with a stem is four whole notes.

Several seem to start with a solo chant in the top voice that is not accounted for in the other parts.

I didn't go through the whole book so I'm not discussing any specific case, but about mensural notation on general :

No barlines is standard (although typically bassus pro organo / partitura parts often do have barlines, although not necessarily consistently or of equal length.)

Robert's note values are correct, for duple meters. In triple time, though, a brevis (square) is divided in 3 semibrevis (whole notes) in tempus perfectum prolatio minor (à circle, or the semibrevis is divided in 3 minime (half notes) in tempus imperfectum prolatio maior (a C with a dot in the middle), or more rarely both, in tempus perfectum prolatio maior (circle with a dot in the middle).

Then there are a bunch of rules that temper that, for example in tempus perfectum a semibrevis after a brevis "imperfects" it (makes it 2 long instead of 3),so a brevis followed by a semibrevis is 2+1. In some cases a semibrevis before a brevis does that too (so it's 1+2), and in some cases, two semibrevis in row will have the second "altered", meaning doubled (also 1+2). It would be hard to explain all these rules in a forum post and they might not all be relevant as this is a rather late source. Black filled notes are always imperfect (duple). (here I notice many pieces start with a solo voice singing a line in black notation - that is chant, as Robert said. It is sometimes accounted for in other parts with rests, sometimes not).

A narrow square note with a stem is a longa (4 whole notes), a wide square note with a stem is a maxima (8 whole notes).

I notice there are ligatures. Those can be rather complex but I've only seen short two note ones in here. Ligatures that have a stem up are always whole-whole. For the others it depends on the shape, direction of motion, and where the last note is relative to the final stem (when there is one).

Note that it is common that not all voices reach the final note at the same time. Those who finish earlier just hang on to their final note until everyone is done.

X is sharp or natural, depending (a B or E with an x is natural, not sharp). Accidentals are rarely used because performers knew where to use them (e.g. sharpen the leading note at cadence, make some Bs and Es flat following the rules of solmisation, etc). They are used inconsistently in written form.

Clefs are the usual F, C and G clefs, except they can be on any line. Standard clef configuration is Soprano Alto Tenor Bass (C1, C3, C4, F4). I notice that some pieces (the very first one for instance) are in what is called "chiavette", literally the "little clefs" - Treble, mezzo soprano, alto, tenor or baritone (G2, C2, C3, C4 or F3). This is generally accepted to mean it would have been transposed down (any piece could be transposed up or down at will, but chiavette often implies it hasto be, and typically by larger transposition interval - down a fourth, fifth, sixth or seventh).

Rests are the hardest part of sight reading music like that (because of the absence of barlines) but are actually the most familiar notation. They are the same we use today. A brevis (square) rest fills the interval between two lines, a longa rest (or two breve) fills two spaces. As we're used to, a semibrevis (whole) rest hangs from the line and minima (half) rest stands on a line - they're just slimmer than the modern version - a semiminima (quarter) rest hooks to the right, and a fusa (8th) rest hooks to the left.

Hope it helped.

-

ttf_Le.Tromboniste

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:59 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Back on topic, "auch andere Magnificat ad equales" would mean "as well as other magnificats in equal voices" (ad is commonly used in this context - for example moteti ad 3, 4 et 5 voces = motets in 3, 4 and 5 voices). The fact that the whole expression is in latin and roman font type while the voicing of the other pieces is previously referred to whithin the German text could be revealing - the editor seems to be referring to a specific genre, however a quick search doesn't come up with any other reference to Magnificat ad voces equales. I don't see any reason to assume equal voices are more relevant to magnificats than other compositions. Writing for an equal voice choir was quite common, whether it's a single choir or within a polychoral composition where you can have a mixture of SATB or SATTB choirs with equal voiced choirs (often ATTB or TTTB, or SSAA, SAAT, or other similar combinations in 3, 4, 5 voices). Clearly this type of voicing is where the later Beethoven and Bruckner "Aequale" or "Equali" draw their origins from. Whether "aequale" as a genre of pieces is an important tradition or not is the question, but I'd start looking closer to Beethoven and Bruckner's time to find a pattern before trying to draw a direct link between them and Renaissance examples of equal voice writing.

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

-

ttf_Le.Tromboniste

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:59 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: robcat2075 on Nov 11, 2017, 09:21AM[s]Any idea what "Peregrini toni" is?[/s]

It means the "ninth tone".

Tonus peregrinus was the ninth mode before Glareanus theoricized about the existence of modes 9 to 12. It was distinct from the other 8 modes in that when reciting in tonus peregrinus, the tenor note moves down (usually one step) for the second phrase. Kind of "modulating", if you want to see it that way (hence the "traveling tone").

Edit : Ha, looked it up as I was answering, did you?

It means the "ninth tone".

Tonus peregrinus was the ninth mode before Glareanus theoricized about the existence of modes 9 to 12. It was distinct from the other 8 modes in that when reciting in tonus peregrinus, the tenor note moves down (usually one step) for the second phrase. Kind of "modulating", if you want to see it that way (hence the "traveling tone").

Edit : Ha, looked it up as I was answering, did you?

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

I guess these mode numbers don't correspond to steps of the scale then?

-

ttf_Le.Tromboniste

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:59 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: robcat2075 on Nov 11, 2017, 09:58AMI guess these mode numbers don't correspond to steps of the scale then?

Not exactly. The original 8 gregorian modes are 1. Dorian, 3. Phrygian, 5. Lydian and 7. Mixolydian, the four "authentic" modes, with 2, 4, 6 and 8 being the plagal version of those four (same names with the "hypo" prefix added). Glareanus came up with modes 9-10 (Aeolian and Hypoaeolian) and 11-12 (Ionian and Hypoionian). It took a while for that to become widespread/mainstream. No mode on B for quite some time after that still.

Not exactly. The original 8 gregorian modes are 1. Dorian, 3. Phrygian, 5. Lydian and 7. Mixolydian, the four "authentic" modes, with 2, 4, 6 and 8 being the plagal version of those four (same names with the "hypo" prefix added). Glareanus came up with modes 9-10 (Aeolian and Hypoaeolian) and 11-12 (Ionian and Hypoionian). It took a while for that to become widespread/mainstream. No mode on B for quite some time after that still.

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: Le.Tromboniste on Nov 11, 2017, 09:36AM... the tenor note moves down (usually one step) for the second phrase. Kind of "modulating", if you want to see it that way (hence the "traveling tone").

I would have trouble identifying that maneuver in any of these parts however.

I would have trouble identifying that maneuver in any of these parts however.

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

When two note heads are connected (a ligature?) that implies a slur on one syllable and the two notes together take half the time they normally would?

-

ttf_BillO

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

There is a wiki article on it. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mensural_notation

It seems incredibly complex but at the same time limiting.

They show a piece there that has each part in a different time signature!!! Sounds kind of cool though.

Sounds kind of cool though.

It seems incredibly complex but at the same time limiting.

They show a piece there that has each part in a different time signature!!!

Sounds kind of cool though.

Sounds kind of cool though.-

ttf_Le.Tromboniste

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:59 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: robcat2075 on Nov 11, 2017, 12:54PMWhen two note heads are connected (a ligature?) that implies a slur on one syllable and the two notes together take half the time they normally would?

No short answer. It often implies a slur on one syllable although not 100% of the time.

And as for note value, as I said it's quite complex, it depends on motion direction, presence or not of stems and if so, their direction, and where the last note is relative to the final stem (if there is one).

It's in any case always a combination of semibreves, breves and/or lunga, never longer or shorter values. Ligature can have as many notes as you want in them. 5 or 6 note ligatures are not uncommon, especially in older repertoire. I'll post examples tomorrow if you want as well as the little memory help with various combinations I have written down somewhere if you'd like. It's late here.

No short answer. It often implies a slur on one syllable although not 100% of the time.

And as for note value, as I said it's quite complex, it depends on motion direction, presence or not of stems and if so, their direction, and where the last note is relative to the final stem (if there is one).

It's in any case always a combination of semibreves, breves and/or lunga, never longer or shorter values. Ligature can have as many notes as you want in them. 5 or 6 note ligatures are not uncommon, especially in older repertoire. I'll post examples tomorrow if you want as well as the little memory help with various combinations I have written down somewhere if you'd like. It's late here.

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

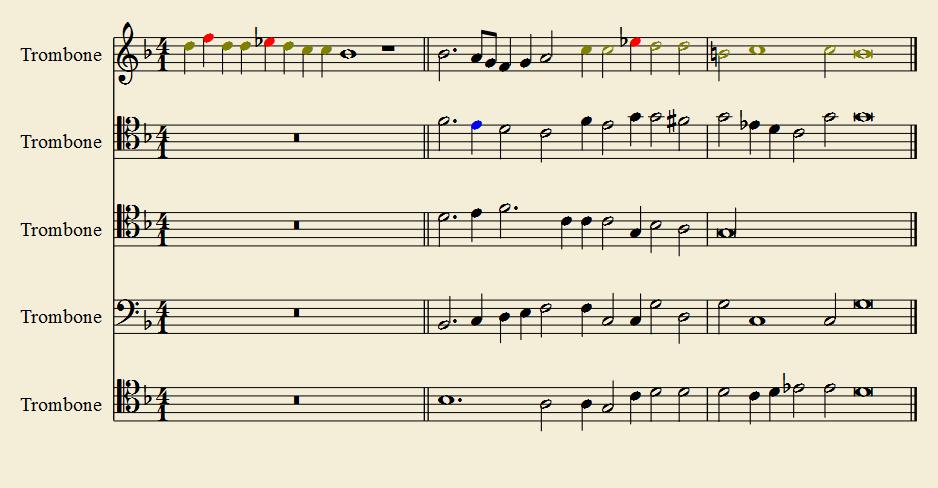

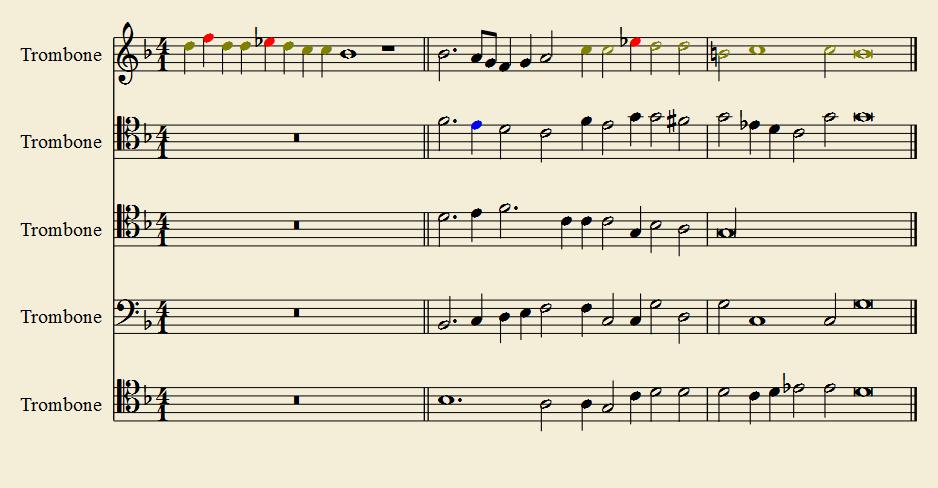

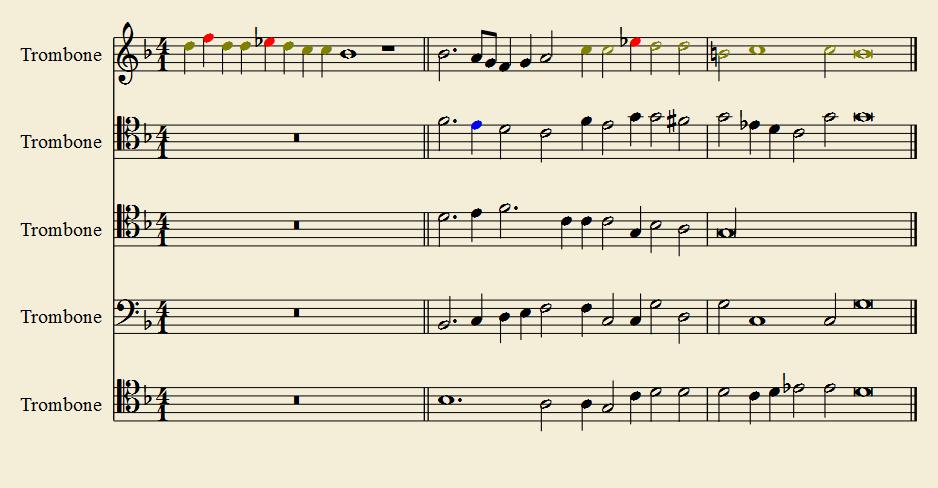

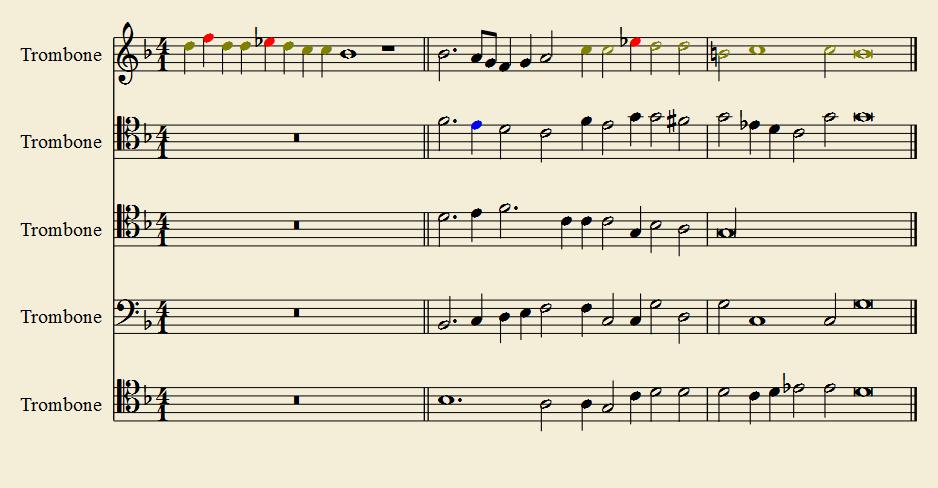

Here's a transcription of the last one in the book, "Ad Peregrinu Tonum Quinq Vocum".

What makes it "Peregrini"?

What makes it "Peregrini"?

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

From what I can glean from this book, the ones prefaced with "Ad aequales" have the voices closer together. More equally matched than SATB ( I guess le tromboniste already pointed that out)

Using the quartet "Die hungrigen" (Peregrinus Tonus)on pg 58 of the Discant book as an example, the highest voice (in the "alto" book) is in mezzo-soprano clef, not treble clef and the lowest voice is in baritone clef rather than bass.

The book contains many different settings of the same few liturgical texts. So maybe the aequale entries allow the option for choirs of only adult men and no boy sopranos or women.

Using the quartet "Die hungrigen" (Peregrinus Tonus)on pg 58 of the Discant book as an example, the highest voice (in the "alto" book) is in mezzo-soprano clef, not treble clef and the lowest voice is in baritone clef rather than bass.

The book contains many different settings of the same few liturgical texts. So maybe the aequale entries allow the option for choirs of only adult men and no boy sopranos or women.

-

ttf_Le.Tromboniste

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:59 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: robcat2075 on Nov 11, 2017, 05:10PMHere's a transcription of the last one in the book, "Ad Peregrinu Tonum Quinq Vocum".

What makes it "Peregrini"?

The chant it's based on.

You see in the given first phrase of chant (discantus book), the "tenor note" is D - that's the first note and the one the chant revolves around. Now the polyphonic stuff is just a setting of the second phrase, which happens to be (almost) intact in the tenor part. Look at that part and you'll see that after repeating the opening D-F motif, the chant goes down to C, which becomes its "main" note, before ending on G a fifth below the initial D. You'll notice that the harmony kind of follows that, it moves from Bb for the opening motif to C, and then cadences to G. That's textbook tonus peregrinus. It's a bit hard to see how the C is the main note of the second phrase here because the whole setting is so short, and the chant is treated rhythmically like the other voices rather than being treated as a cantus firmus.

However if you go back in the book the the whole section of German magnificats in Tonus perigrinus, you'll find other settings of the same chant. This is the quinta pars of one of them, p. 39 of the Bassus book.

It is the same chant, treated a fourth lower (more on that below) and with the chant used strictly as a cantus firmus, which makes it much more obvious. (it starts with the first phrase recited in the discantus again, but then both phrases alternate, always in the quinta pars.) It is very clear - first phrase always insists on A, then second phrase inists on G and cadences down to D.

It is a fourth lower because it is in chiavi naturali (soprano, alto, tenor, (tenor,) bass). The example you transcribed, meanwhile, was in chiavette (Treble, mezzo, alto, (alto,) baritone). It would have likely been sung or played transposed down - a fourth would make sense given the ranges and the previous treatments of the same chant.

What makes it "Peregrini"?

The chant it's based on.

You see in the given first phrase of chant (discantus book), the "tenor note" is D - that's the first note and the one the chant revolves around. Now the polyphonic stuff is just a setting of the second phrase, which happens to be (almost) intact in the tenor part. Look at that part and you'll see that after repeating the opening D-F motif, the chant goes down to C, which becomes its "main" note, before ending on G a fifth below the initial D. You'll notice that the harmony kind of follows that, it moves from Bb for the opening motif to C, and then cadences to G. That's textbook tonus peregrinus. It's a bit hard to see how the C is the main note of the second phrase here because the whole setting is so short, and the chant is treated rhythmically like the other voices rather than being treated as a cantus firmus.

However if you go back in the book the the whole section of German magnificats in Tonus perigrinus, you'll find other settings of the same chant. This is the quinta pars of one of them, p. 39 of the Bassus book.

It is the same chant, treated a fourth lower (more on that below) and with the chant used strictly as a cantus firmus, which makes it much more obvious. (it starts with the first phrase recited in the discantus again, but then both phrases alternate, always in the quinta pars.) It is very clear - first phrase always insists on A, then second phrase inists on G and cadences down to D.

It is a fourth lower because it is in chiavi naturali (soprano, alto, tenor, (tenor,) bass). The example you transcribed, meanwhile, was in chiavette (Treble, mezzo, alto, (alto,) baritone). It would have likely been sung or played transposed down - a fourth would make sense given the ranges and the previous treatments of the same chant.

-

ttf_Le.Tromboniste

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:59 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: robcat2075 on Nov 11, 2017, 08:54PMFrom what I can glean from this book, the ones prefaced with "Ad aequales" have the voices closer together. More equally matched than SATB ( I guess le tromboniste already pointed that out)

Using the quartet "Die hungrigen" (Peregrinus Tonus)on pg 58 of the Discant book as an example, the highest voice (in the "alto" book) is in mezzo-soprano clef, not treble clef and the lowest voice is in baritone clef rather than bass.

The book contains many different settings of the same few liturgical texts. So maybe the aequale entries allow the option for choirs of only adult men and no boy sopranos or women.

Same here, that one might well have been sung or played transposed down - mezzo-alto-alto-baritone is a standard chiavette combination for equal voices

Using the quartet "Die hungrigen" (Peregrinus Tonus)on pg 58 of the Discant book as an example, the highest voice (in the "alto" book) is in mezzo-soprano clef, not treble clef and the lowest voice is in baritone clef rather than bass.

The book contains many different settings of the same few liturgical texts. So maybe the aequale entries allow the option for choirs of only adult men and no boy sopranos or women.

Same here, that one might well have been sung or played transposed down - mezzo-alto-alto-baritone is a standard chiavette combination for equal voices

-

ttf_Le.Tromboniste

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:59 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: robcat2075 on Nov 11, 2017, 12:54PMWhen two note heads are connected (a ligature?) that implies a slur on one syllable and the two notes together take half the time they normally would?

Here's that little helper I had written to myself to remember.

Sorry for my bad calligraphy, this was meant for me to read back

I haven't noticed any ligatures with more than 2 notes in this book so you should have all possibilities on there. If there were any that are more than two notes, everything in the middle is breves.

Here's that little helper I had written to myself to remember.

Sorry for my bad calligraphy, this was meant for me to read back

I haven't noticed any ligatures with more than 2 notes in this book so you should have all possibilities on there. If there were any that are more than two notes, everything in the middle is breves.

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: Le.Tromboniste on Nov 12, 2017, 04:30AMHere's that little helper I had written to myself to remember...

thanks!

thanks!

-

ttf_kbiggs

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:53 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Back to the word equali or aequali...

1. It seems to be a type of composition, and not a style of composition.

2. What is meant or intended by the word seems to have changed over time. That is, either the thing the word referred to changed, or the word started to be used differently.

This second point is, I think, very important in this discussion. There are lots of things out there (in museums, attics, etc.) that had a specific meaning at one time, or perhaps a particular meaning at a specific time and place, that have essentially become meaningless today. Examples might be halberd from ancient weaponry, or mullion from castle-building. We know today what they are because of extant records. But they have little meaning in todays world. (An exception to mullion: side-by-side refrigerators sometimes have them to ensure a proper seal.)

Im beginning to view the word equali or aequali like we use the word/s sackbutt, sackbut, sacbut, shagbutt, saquebouche, etc. What it meant when it was used is different from what we understand today. Today, the word sackbutt, sackbut, sacbut, etc. has come to mean something like, the trombone as it was before ca. 1750, or the immediate progenitor of the trombone.

Perhaps equali were a type of composition that had some use or purpose at one time which has been lost to history. Or, perhaps the term equali wasnt applied consistently, and were left with an ill-defined, sporadically used term from history that has little meaning today.

1. It seems to be a type of composition, and not a style of composition.

2. What is meant or intended by the word seems to have changed over time. That is, either the thing the word referred to changed, or the word started to be used differently.

This second point is, I think, very important in this discussion. There are lots of things out there (in museums, attics, etc.) that had a specific meaning at one time, or perhaps a particular meaning at a specific time and place, that have essentially become meaningless today. Examples might be halberd from ancient weaponry, or mullion from castle-building. We know today what they are because of extant records. But they have little meaning in todays world. (An exception to mullion: side-by-side refrigerators sometimes have them to ensure a proper seal.)

Im beginning to view the word equali or aequali like we use the word/s sackbutt, sackbut, sacbut, shagbutt, saquebouche, etc. What it meant when it was used is different from what we understand today. Today, the word sackbutt, sackbut, sacbut, etc. has come to mean something like, the trombone as it was before ca. 1750, or the immediate progenitor of the trombone.

Perhaps equali were a type of composition that had some use or purpose at one time which has been lost to history. Or, perhaps the term equali wasnt applied consistently, and were left with an ill-defined, sporadically used term from history that has little meaning today.

-

ttf_Le.Tromboniste

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:59 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: kbiggs on Nov 12, 2017, 09:39AMBack to the word equali or aequali...

1. It seems to be a type of composition, and not a style of composition.

2. What is meant or intended by the word seems to have changed over time. That is, either the thing the word referred to changed, or the word started to be used differently.

This second point is, I think, very important in this discussion. There are lots of things out there (in museums, attics, etc.) that had a specific meaning at one time, or perhaps a particular meaning at a specific time and place, that have essentially become meaningless today. Examples might be halberd from ancient weaponry, or mullion from castle-building. We know today what they are because of extant records. But they have little meaning in todays world. (An exception to mullion: side-by-side refrigerators sometimes have them to ensure a proper seal.)

Im beginning to view the word equali or aequali like we use the word/s sackbutt, sackbut, sacbut, shagbutt, saquebouche, etc. What it meant when it was used is different from what we understand today. Today, the word sackbutt, sackbut, sacbut, etc. has come to mean something like, the trombone as it was before ca. 1750, or the immediate progenitor of the trombone.

Perhaps equali were a type of composition that had some use or purpose at one time which has been lost to history. Or, perhaps the term equali wasnt applied consistently, and were left with an ill-defined, sporadically used term from history that has little meaning today.

The thing is, there are very few referenced to the term "aequali" as a type of piece.

The much earlier "ad aequales" previously discussed most definitely doesn't designate a type of composition.

1. It seems to be a type of composition, and not a style of composition.

2. What is meant or intended by the word seems to have changed over time. That is, either the thing the word referred to changed, or the word started to be used differently.

This second point is, I think, very important in this discussion. There are lots of things out there (in museums, attics, etc.) that had a specific meaning at one time, or perhaps a particular meaning at a specific time and place, that have essentially become meaningless today. Examples might be halberd from ancient weaponry, or mullion from castle-building. We know today what they are because of extant records. But they have little meaning in todays world. (An exception to mullion: side-by-side refrigerators sometimes have them to ensure a proper seal.)

Im beginning to view the word equali or aequali like we use the word/s sackbutt, sackbut, sacbut, shagbutt, saquebouche, etc. What it meant when it was used is different from what we understand today. Today, the word sackbutt, sackbut, sacbut, etc. has come to mean something like, the trombone as it was before ca. 1750, or the immediate progenitor of the trombone.

Perhaps equali were a type of composition that had some use or purpose at one time which has been lost to history. Or, perhaps the term equali wasnt applied consistently, and were left with an ill-defined, sporadically used term from history that has little meaning today.

The thing is, there are very few referenced to the term "aequali" as a type of piece.

The much earlier "ad aequales" previously discussed most definitely doesn't designate a type of composition.

-

ttf_robcat2075

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 11:58 am

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

Quote from: kbiggs on Nov 12, 2017, 09:39AMBack to the word equali or aequali...

1. It seems to be a type of composition, and not a style of composition.

By Bruckner's time it is clearly both. A solemn, mostly homophonic piece for trombone choir. Within 4 years of each other Bruckner and Lambel compose things that fit that outline and explicitly call them that. They both use the word in this way and yet we know of no other examples prior to them to establish that meaning.

Maybe it meant that to Beethoven also, but it doesn't appear he actually called his pieces "equale"

Quote2. What is meant or intended by the word seems to have changed over time. That is, either the thing the word referred to changed, or the word started to be used differently....

Perhaps equali were a type of composition that had some use or purpose at one time which has been lost to history. Or, perhaps the term equali wasnt applied consistently, and were left with an ill-defined, sporadically used term from history that has little meaning today.

I agree that words change over time.

I see the Giovanni Pinello set as maybe representing the first step in the evolution of the term. It's an interesting fish on the beach but we don't know if it grew legs after that and continued on.

What we would need to see are pieces from 1600-1800 that more resemble our expectations and use the word in the way the legend has told us it was being used.

1. It seems to be a type of composition, and not a style of composition.

By Bruckner's time it is clearly both. A solemn, mostly homophonic piece for trombone choir. Within 4 years of each other Bruckner and Lambel compose things that fit that outline and explicitly call them that. They both use the word in this way and yet we know of no other examples prior to them to establish that meaning.

Maybe it meant that to Beethoven also, but it doesn't appear he actually called his pieces "equale"

Quote2. What is meant or intended by the word seems to have changed over time. That is, either the thing the word referred to changed, or the word started to be used differently....

Perhaps equali were a type of composition that had some use or purpose at one time which has been lost to history. Or, perhaps the term equali wasnt applied consistently, and were left with an ill-defined, sporadically used term from history that has little meaning today.

I agree that words change over time.

I see the Giovanni Pinello set as maybe representing the first step in the evolution of the term. It's an interesting fish on the beach but we don't know if it grew legs after that and continued on.

What we would need to see are pieces from 1600-1800 that more resemble our expectations and use the word in the way the legend has told us it was being used.

-

ttf_MrPillow

- Posts: 0

- Joined: Sat Mar 31, 2018 12:00 pm

The Mystery of the Missing Equali

There seem to be numerous compositions and arrangements from the 17th and early 18th century in the German that call for "gleiche Instrumente," or songs for sets of the same instrument (sometimes voices). This seems more close in practice to the "equali" model of a set of trombones, but stylistically they range far beyond the solemn and somber funeral music and the word "equali" in any version is nowhere to be found.